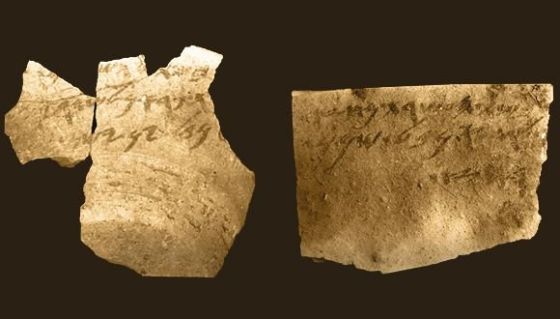

The ancient Samaria ostraca — eighth-century BCE ink-on-clay inscriptions unearthed at the beginning of the 20th century in Samaria, the capital of the biblical kingdom of Israel — are among the earliest collections of ancient Hebrew writings ever discovered. But despite a century of research, major aspects of the ostraca remain in dispute, including their precise geographical origins — either Samaria or its outlying villages — and the number of scribes involved in their composition.

A new Tel Aviv University study found that just two writers were involved in composing 31 of the more than 100 inscriptions and that the writers were contemporaneous, indicating that the inscriptions were written in the city of Samaria itself.

Research for the study was conducted by Ph.D. candidate Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin, Dr. Arie Shaus, Dr. Barak Sober and Prof. Eli Turkel, all of TAU’s School of Mathematical Sciences; Prof. Eli Piasetzky of TAU’s School of Physics; and Prof. Israel Finkelstein, Jacob M. Alkow Professor of the Archaeology of Israel in the Bronze and Iron Ages, of TAU’s Sonia and Marco Nadler Institute of Archaeology.

A palace bureaucracy

The inscriptions list repetitive shipment details of wine and oil supplies to Samaria and span a minimal period of seven years. For archaeologists, they also provide critical insights into the logistical infrastructure of the kingdom of Israel. The inscriptions feature the date of composition (year of a given monarch), commodity type (oil, wine), name of a person, name of a clan and name of a village near the capital. Based on letter-shape considerations, the ostraca have been dated to the first half of the eighth century BCE, possibly during the reign of King Jeroboam II of Israel.

“If only two scribes wrote the examined Samaria texts contemporaneously and both were located in Samaria rather than in the countryside, this would indicate a palace bureaucracy at the peak of the kingdom of Israel’s prosperity,” Prof. Finkelstein explains.

“Our results, accompanied by other pieces of evidence, seem also to indicate a limited dispersion of literacy in Israel in the early eighth century BCE,” Prof. Piasetzky says.

When math solves history

“Our interdisciplinary team harnessed a novel algorithm, consisting of image processing and newly developed machine learning techniques, to conclude that two writers wrote the 31 examined texts, with a confidence interval of 95%,” said Dr. Sober, now a member of Duke University’s mathematics department.

Prof. Israel Finkelstein at a TAU dig in Megido

“The innovative technique can be used in other cases, both in the Land of Israel and beyond. Our innovative tool enables handwriting comparison and can establish the number of authors in a given corpus,” adds Faigenbaum-Golovin.

The new research follows up from the findings of the group’s 2016 study, which indicated widespread literacy in the kingdom of Judah a century and a half to two centuries later, circa 600 BCE. For that study, the group developed a novel algorithm with which they estimated the minimal number of writers involved in composing ostraca unearthed at the desert fortress of Arad. That investigation concluded that at least six writers composed the 18 inscriptions that were examined.

“It seems that during these two centuries that passed between the composition of the Samaria and the Arad corpora, there was an increase in literacy rates within the population of the Hebrew kingdoms,” Dr. Shaus says. “Our previous research paved the way for the current study. We enhanced our previously developed methodology, which sought the minimum number of writers, and introduced new statistical tools to establish a maximum likelihood estimate for the number of hands in a corpus.”