TAU Excavation Examines “Ancient High Tech”

Plant remains elucidate early Israel’s role in global metals industry.

By Melanie Takefman

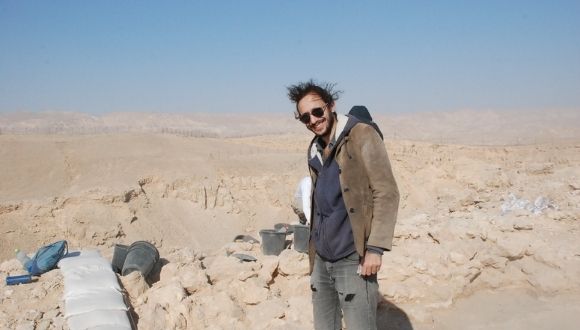

The wind is the first to “welcome” visitors to the hilltop TAU excavation at Yotvata, a kibbutz in the Arava desert. It lashes out at anyone or anything in its path, merciless. The steep ascent to the site is no more hospitable.

“This site is here precisely for this reason,” explains Mark Cavanagh, a doctoral candidate at TAU’s Chaim Rosenberg School of Jewish Studies and Archaeology. “The winds powered the smelting furnaces—fanned the flames—in the early periods of the copper industry.” The dig at Yotvata is part of TAU’s Central Timna Valley Excavation, led by Prof. Erez Ben-Yosef. Since 2012, Ben-Yosef and his team have studied the ancient mining industry in Israel’s South, which peaked around 1,000 BCE, during the time of Biblical kings David and Solomon. During the current dig season, the Timna Valley team is studying the earlier stages, in the third millennium BCE, of what Ben-Yosef refers to as the “high tech of the ancient world.”

The wind is the first to “welcome” visitors. TAU excavation at Yotvata

“We’re interested in how the metallurgical industry started,” says Ben-Yosef. His team has found evidence that the early mines’ products served the Egyptian empire. “The elite needed luxury materials such as jewelry, tools and ornaments… copper was part of the social processes that made civilizations and empires.”

According to his hypothesis, the communities surrounding Timna were much more important than previously thought because they had ties to the “great Egypt of the pyramids,” Ben-Yosef says. Moreover, their prominence points to the crucial role of the metal’s industry in the emergence of the Egyptian empire as well as the first urban societies, which developed at around that time in northern and central Israel.

Cavanagh, a New Jersey native, is an archaeobotanist, studying plant remains to learn about the past. He completed an International MA in Archaeology at TAU and is now in the second year of his PhD at TAU, under the supervision of Ben-Yosef and Dr. Dafna Langgut.

At Timna, Cavanagh seeks vestiges of the fuel sources that fed the copper smelting furnaces. By analyzing them, he gleans insights into the broader context of the mines and the role they played in the third millennium BCE. For example, the types of plant remains he finds can tell him about that period’s ecology and climate. Through traces of pollen, for example, he hopes to learn if the area was more savannah-like 5,000 years ago.

One of the season’s exciting finds was a grave attributed to the Early Bronze Age at Yotvata. Through it, Cavanagh hopes to learn more about the inhabitants of the mining site. “The entire area is covered in graves.” Together, they create a path that indicates travel routes. “We’ll begin to understand the tracks that people were taking in the Early Bronze Age,” he says, both in terms of trade and migration.

Each of these elements, pieced together, will shed light onto what Cavanagh calls “one of the greatest stories of human history: How and when and why did people learn to turn pretty rocks into useful metal?“

Stay tuned for the next season!

Featured image: hilltop TAU excavation at Yotvata

Related posts

Empowering Israeli-Arab Students in Humanities